OK Boomers!

To be (Syrian), or not to be? That’s the question

Landa Ruweha

1/17/20223 min read

Felicity Huffman once described her preparation for her role in Transamerica as “a lesson in learning femininity as if it were a foreign language.”

I never got the chance to watch that film, but the metaphor was etched into my memory since first hearing it because it described my cultural catch-22 to a tee.

You see, theoretically, identifying as a Syrian should be an open-and-shut case for me:

My dad was Syrian born and bred.

I had lived there for 25 years until I left for good in 2009 (I was 35 then so +70% of my life)

I got my schooling in Syrian schools from KG until I received my Baccalaureate.

I have friends, family even my (former) in-laws.

So why is it that I’ve always felt a sense of confusion, even dread, whenever I was asked: “Where are you from?”

But that’s what happens when you have rebels for parents.

My father left his sleepy hometown town of Latakia when he was 18 to study civil engineering in Cairo, the largest metropolis in the Arab world, a Hollywood on the Nile that turned him into a dashing debonair who’d always strive to live life to its fullest.

A year after graduating, he’d meet my mum in her native Tripoli, the capital of Libya. She was still studying and would become the first female civil engineer in her country.

At that time, Libya was a very conservative country even by Arab standards where most women were still wearing the traditional Firrashiyya. It was a North African version of the Burqa that looked like a white tent which only allowed a woman to show ONE eye!

My mum? She was walking around in fashionably coifed hair wearing mini dresses, often sleeveless. It’s not a surprise she was nicknamed Jeanne D’arc.

She was doing a postgraduate course in London when they decided to get married in 1969, tying the knot in Beirut, Lebanon then moving to Abu Dhabi where my dad had a lucrative construction contract. They returned to London for my birth, then the whole family relocated to Libya for a year before my was forced to leave so we headed back to Latakia.

Despite the political restrictions and the limited business opportunities due to Latakia’s relatively small size, Dad managed to provide for us a lifestyle that was the envy of the whole city. He may have not been among the richest men in town but he lived like a king!

Looking back at those years, I’m humbled by the immense privilege we enjoyed. But my mum regarded Latakia the same way Napoleon must’ve thought of Saint Helena; she found it small and suffocating and she did not hide her disdain for the place and (most of) its people.

As a result, she chose to have a circle that was mostly mixed couples of Syrians married to Europeans. I had a Czech paediatrician, a Bulgarian dentist and a Russian piano teacher and an Armenian hairdresser. Dad was a Europhile through and through so that was ok with him. Slowly, our home became a cultural bubble that bore little resemblance to the society around us.

On the one hand, this made our lives richer and more interesting but on the other hand, it was like being in a Aeroponics lab where plants are grown with naked roots, with no soil, no sunlight, never to experience the elements or the cycles of Nature.

With age, I realised that I had become a Schrödinger's cat of sorts; a native and an alien at the same time.

After decades of trying to banish the alien, I had to make peace with it and accept it will always be a part of me. But there was one place where I was determined to reclaim my Syrian identity:

the kitchen.

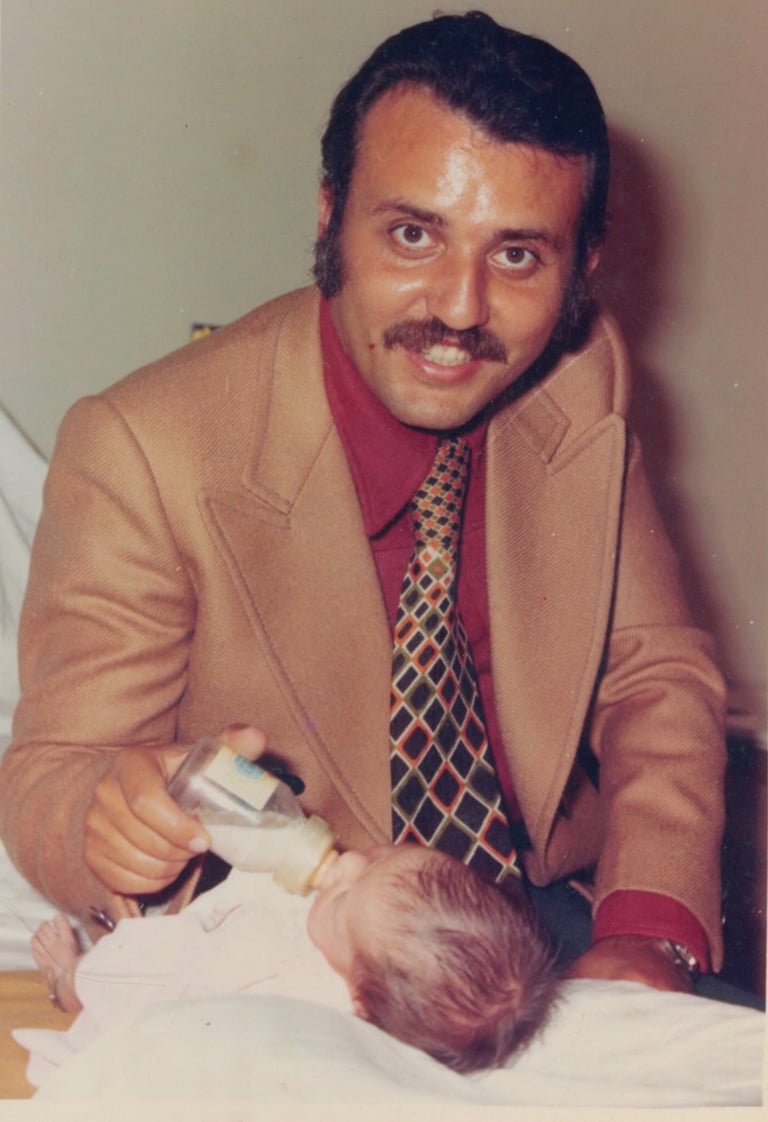

Dad and newborn me at the hospital in London