Through the Looking Glass

Exploring my own version of Wonderland

Landa Ruweha

1/25/20223 min read

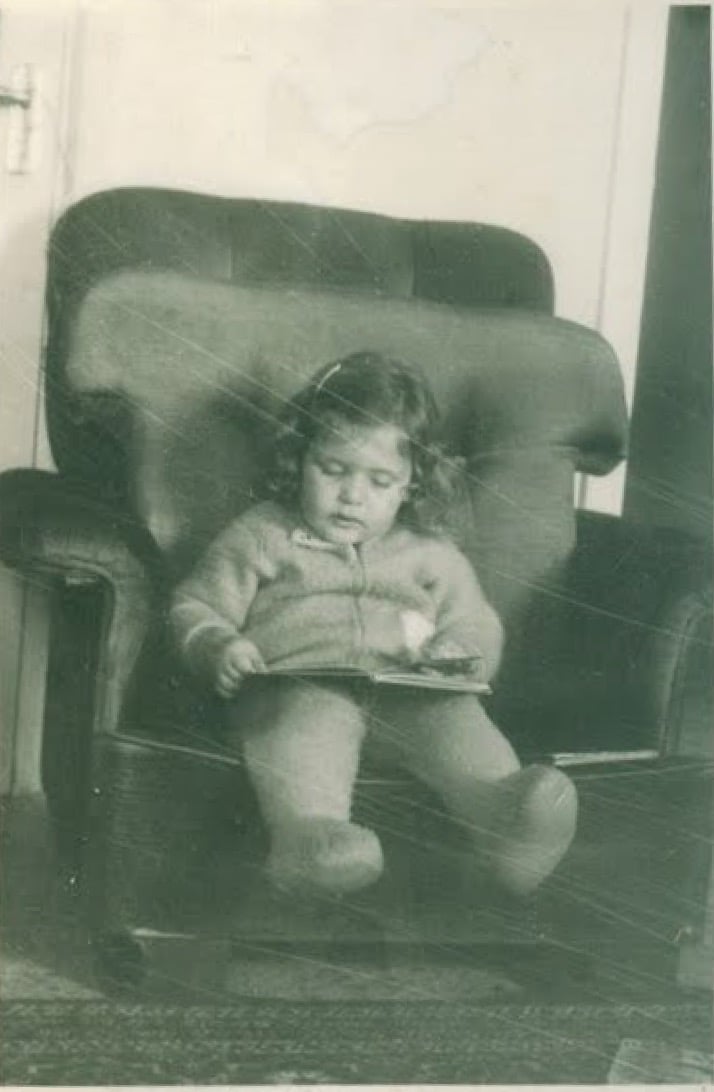

I was 2.5 years old when my parents sent me to school. It was prep year (what Poles call zerówka) but it still counted as regular school.

I was already fluent in both Arabic and English at that age - and I think I could read and write in English because I’d write Arabic words from left to right- so my parents thought school work wouldn’t be a stretch for me. It wasn’t. I enjoyed learning but this meant I’d go through my entire school tenure as the youngest kid in class- often 2 years younger than the others.

That, and being culturally “out of sync”, made me extremely anxious, shy and introverted. Having two strong-willed parents didn’t help. I often felt like “a shrimp between two whales” as the Koreans describe their country’s geopolitical position. I’d spend every free moment with my nose buried in a book or keeping busy with some kind of craft.

Why am I telling you all that? Because despite being a human manifestation of a hermit crab, I was willing to venture out of my shell if food was involved. I don’t mean eating, I was never much of a big eater, but I was fascinated by the Syrian idiosyncrasies around food.

It was little things like putting salt in a small saucer instead of using a salt shaker or how people spread out fresh pita bread that they had just got from the bakery on any low wall they could find so it’d cool down before packing it. The bread would be sitting there exposed to smog and dust and they’d tear a piece o! and eat it blissfully.

Then there are those folks who go to a restaurant and instead of ordering a salad, they ask for a bowl of fresh veggies that they peel and slice themselves because they don’t trust the staff to have washed the vegetables to their satisfaction - or worse, that they might’ve used citric acid in the dressing instead of fresh lemon juice.

And if the meal at the restaurant was an invite, then the merry mood would turn suddenly violent when it was time to pay the bill, with hand-to-hand combat as the men try to snatch the check from the poor waiter’s hand and loudly vow to divorce their wives if they don’t get to pay.

Whether I was tagging along for my dad’s trips to the market for local treats or enjoying a culinary escape at a restaurant or at friends’ homes, food became an Ariadne’s thread that I used to explore the underbelly of Syrian society and culture.

At first, I was merely noting all that caught my eye and tickled my palette. I’d make mental snapshots and try to memorize the flavors. Later on, I started to ask questions and began to recognize patterns and, with time, the pull of that strange world was getting stronger while I was becoming more and more dissatisfied with how we did things at home.

My mum always said: “We eat to live not live to eat”. It was a saying that summed up her disdain not just for cooking but for eating too. She tried to drill that mantra into me, thinking that by repeating it enough, she’d cure me of my romantic approach to food. I knew better than to argue with her. She had a binary view of the world, I had kaleidoscopes for eyes.

I remember coming home from school. Our apartment was on the fifth floor but I loved to take the stairs instead of the elevator so I could catch a whiff of what the neighbours were cooking. You could tell by the smell what each family was having for lunch that day. It was like a relay race of aromas as I climbed from one floor to the next until I got to the last flight of stairs before our apartment and the trail of scents would go cold.

There was no smell when I’d enter the apartment either. I’d have to go into the kitchen where the food was under arrest in the shiny stainless steel pots, and only then would I finally know what’s for lunch.

Don’t get me wrong, my mum could cook delicious food, but I wasn’t feeling it. There was obviously more to food than a good taste, and I was determined to find what it was.